Injuries to the articulations of the midfoot are not uncommon and thus are occasionally overlooked or misdiagnosed. The consequences of inadequate treatment, however, can be unsuspected until irreversible damage has been done to the patient. Optimal functional outcome can only be assured if Lisfranc articulation injuries are rapidly recognized and appropriately treated. This article serves to review the anatomy of the region, to define Lisfranc injuries, to document both the unusual frequency and potential severity of associated complications, and to familiarize the reader with common clinical and radiographic patterns of presentation. Practical management guidelines are offered to assist the surgeon in evaluating and treating these complex injuries. Clinical and physical examination methods are described, as well as appropriate methods for evaluating foot radiographs. Finally, a staged treatment regimen is proposed, offering methods for both urgent and delayed realignment and reconstruction of the injured Lisfranc articulations.

Lisfranc fractures involving the tarsometatarsal joint complex may be overlooked or inadequately treated. Nonrecognition of their presence and subsequent inadequate treatment can result in significant loss of function and chronic pain. Such fractures represent a spectrum of joint injuries ranging from purely ligamentous disruption through varying degrees of osseous-soft tissue trauma to outright complete dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joint. Fracture-dislocations represent the more severe and disabling forms of these injuries and require rapid and accurate diagnosis followed by prompt treatment. The clinician evaluating injuries to the area must have a high index of suspicion, be aware of their frequency, recognize the vast spectrum of injury, rely on a detailed knowledge of normal anatomy as well as common pathologic patterns and, finally, be alert to potential complications.

The midtarsal bony and ligamentous complex bears a significant mechanical role both in even and uneven surfaces and in the transition from the stance phase to the swing phase. Throughout these gait motions, the subtalar joint, the Lisfranc joint complex, and the transmetatarsal joint are constantly working to coordinate and absorb the forces. Numerically, the midtarsal joint complex comprises nearly a quarter of the transverse-plane subtalar joint motion. Moreover, the curvature shape in the metatarsal heads acts like a “cam” hinge which is translated to significant plantarflexion-dorsiflexion motion. This array of muscle pulls collaborates in introducing significant force-related potential levers. The effectiveness of the force elongation and shortening transformers narrows when the muscle is inserted into individual metatarsals.

The Lisfranc joint complex includes the articulation between the medial and intermediate cuneiform bones and the bases of the second metatarsal. The ligamentous structures attaching to the medial cuneiform are well demonstrated on anatomic dissections and are more substantial than the more commonly appreciated second metatarsal tarsometatarsal articulation. However, the medial cuneiform articular surface is at a more coronal plane than the corresponding second metatarsal joint surface. The bony congruity established between the cuneiform bones and the second metatarsal permit the complex to transfer the rearfoot loads into the forefoot and toes without significant disruption at the midfoot. Cranially, these forces are largely accommodated by the windlass mechanism provided by the plantar flexion of the first metatarsal, metatarsal-cuneiform articulation, and the tensioning of the plantar aponeurosis.

The stability, functional axis, and anatomic relationships of the bones around the Lisfranc joint complex have important mechanical and kinetic consequences on the plantar arch and phalangeal function. Even though the middle and the hindfoot work in unison as a lever during the push-off phase of gait, the first ray has to act individually as a strut, inducer, and stabilizer for the deformable lever of the remaining toes, stabilizing the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, augmenting the windlass mechanism, leading to the propulsive, balance, and impulsion functions of the foot. Hence, Lisfranc joint injuries, the repeated ligamentous failure at that site in high-level athletes, and the resultant instability of the complex may have deleterious effects on the whole foot and the gait cycle.

The Lisfranc joint represents the bony and ligamentous connection between the forefoot and the midfoot and is essential for the maintenance of a stable and functional foot. The Lisfranc complex includes the three cuneiform bones, the second through the fifth rays and the metatarsal basements, and it is maintained by a series of plantar, interosseous, and dorsal ligaments, which act in a coordinated way with the extrinsic and intrinsic flexor and extensor musculature. This structure allows the transmission of weightbearing forces from the hindfoot to the forefoot, the ligamentous recoil after foot strike, and the customized bone movement pattern and tendon glide during the midstance, push-off, and swing phases of the gait cycle. The unique functional preparation and ligamentous connections between the Lisfranc joint bones are responsible for the nonaxial configuration allowing the propulsive

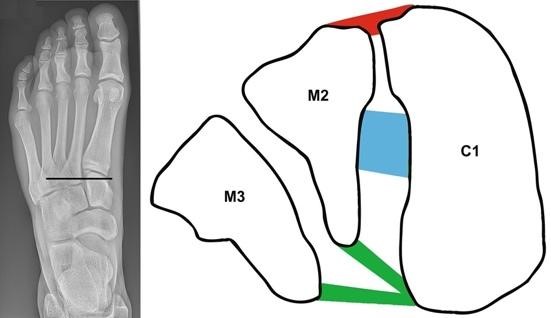

Tarsometatarsal joints include the joints between the M1 and the tarsal bones including the medial cuneiform (MCC), the second tarsometatarsal joint between the M2 and the central cuneiform (CC), the tarsometatarsal joint between the M3 and the lateral cuneiform (LC), and so forth. However, the first tarsometatarsal joint (M1 and MCC) and the second tarsometatarsal joint (M2 and CC) are often cited in different studies, as they represent where most traumatic Lisfranc injuries occur.

The foot consists of five metatarsal bones, as named and numbered from medial to lateral: the first metatarsal (M1), the second metatarsal (M2), the third metatarsal (M3), the fourth metatarsal (M4), and the fifth metatarsal (M5). Each of the metatarsal bones connects to the tarsal bones on the posterior part of the foot via what is known as the tarsometatarsal joints. A joint is where two bones are attached and provides the bone with flexion and extension mobility. In this region, the tarsometatarsal joint is also known as the Lisfranc joint.

The high energy and commonly axial load to the foot that causes a Lisfranc injury are often secondary to a motor vehicle collision or a fall from a significant height. A low energy mechanism of injury includes a twist to the fixed foot with weight placed on the heel, such as the foot caught in a stirrup while trailing or being thrown from a horse. Although direct force is not commonly seen as a leading cause, direct force from an assault like the foot placed on a potential victim does occur and direct force from industrial crush or injury is also seen. The severity and direction of the force sustained dictates the resultant pathology and required treatment modalities. Acute injuries usually occur in young to middle-aged males secondary to a high energy trauma. The chronic form is more common in middle-aged females and older adults. The type of injury is also influenced by the integrity of the bones. The reduction of anatomic structures and the maintenance of fixation can only be established when bony fragments are large enough and structurally sound. The severely weakened and fragmented osteoporotic bone seen in the elderly compromises the fixation because underfunctional fixation implants may be required, which ultimately do not contain or address the injury. Spontaneous necrosis of the tarsometatarsal joint complex is a rare entity that occurs in adults without major trauma or history of radiation therapy. Most patients present with vague symptoms and the bizarre radiographic appearance and unlamentable history of many of the patients makes this disease process easy to manage when performed in a teaching institution.

The second factor influencing the decision-making was, of course, the surgeon’s specific hypothesis and treatment technique in the individual case. All of the participating surgeons possessed thorough expertise in harm, microsurgery of vessels and nerves, as well as cruciate ligament reconstructions. The combination of relevant morphological characteristics (high-velocity trauma, soft tissue damage) as well as different surgical techniques (long dorsal plate, screw versus screw and plate osteosynthesis) has led to the situation that the fact its influence on a given fracture might be neglected in some reports. As this particular research was conducted solely by the investigators specialized in foot surgery, the above-mentioned factors were not present in this study, while it was devised to focus only on the intraoperative axis assessment. All axis cephalo-caudal deviations were noted.

The frequency and character of other intercarpal fracture-dislocation injuries were described previously. This study aimed to compare the frequency of unequal contribution of each axis between conventional and lockable plates. Differences reflect population variability. We performed a retrospective comparison of radiographic parameters in a large series of patients who had sustained bilateral Lisfranc fractures or dislocations. In each patient, one Lisfranc fracture or dislocation was fixed with a conventional plate; the other, using a locking/compression plate. FormData were gathered for three tibial shaft fractures – the same collection used in previous publications. There were no statistical differences concerning the patient’s age or sex. The fracture characteristics were similar (open versus closed harm, AO, and Gustilo classification, the severity of soft tissue damage).

Physical examination should include careful evaluation of the injured foot as well as the contralateral foot. Swelling and ecchymosis about the midfoot, as well as plantar ecchymosis near the base of the first metatarsal, are often observed. On physical examination, they do not have problems moving their toes, but they do have pain when moving the bones behind the toes (when doing this type of examination, the examiner is typically moving the patient’s toes upwards to force the metatarsal heads to compress the midfoot from below). Upon clinical examination of the asymptomatic contralateral foot, such evaluation often reproduces the discomfort felt on the affected side. Such suspected injuries should be immobilized and deemed non-weight-bearing, with further evaluation via radiologic studies. Overall, the diagnosis of these injuries usually involves the utilization of radiographs, including weight-bearing series.

The diagnosis of Lisfranc fracture-dislocations can be challenging. Moreover, these injuries can often be missed at the initial examination. Typically, a patient walks in with an abduction force (usually a twist) which injures the transverse forefoot metatarsus. A high index of suspicion is essential. Patients with ligamentous Lisfranc disruptions complain of significant pain, and the foot is often deformed. Non-weight-bearing on the affected side is generally observed, but those who are able to walk may do so with a suggestion of being on their toes. Ecchymosis and swelling may or may not be present. Both the dorsal aspect of the midfoot and the plantar aspect of the midfoot are often relatively spared of cutaneous bruising.

Walking is difficult and there is usually a substantial limp. If you have a primary concern for a Lisfranc injury, don’t consider it a simple sprain because any delay in diagnosing and treating a Lisfranc fracture-dislocation may have long-term, debilitating consequences. The best person to recognize a Lisfranc injury is a specialist in orthopaedic surgery because they have experience treating these uncommon but complex injuries. About 20% of cases are not diagnosed, resulting in an unstable foot with chronic pain and swelling. It is always best to seek the aid of a competent healthcare professional who has experience diagnosing and treating this kind of injury. A flawed treatment plan for a Lisfranc injury provides a poor outcome, resulting in long-term pain and a destabilized midfoot.

A Lisfranc injury is very painful and can be confused with simple sprains, but the injury to the ligament complex is severe and might include many damaged structures. Pain and swelling develop immediately after the injury and may disappear later. Bruising of both the top and bottom of the foot occurs, which is a useful physical sign to help the doctor diagnose a Lisfranc injury. Flat bones (tarsals) in the midfoot may be crushed after releasing some or all of the ligament’s attachments. It is important for the doctor to understand how the injury occurred to assess patterns of potential ligament disruption that aid in directing repairs for the resulting instability of the midfoot.

As for diagnostic imaging, the preferred primary modality is radiographs that are best obtained in the form of a minimum of three views (AP, 30° oblique, and lateral) of the affected foot. A weight-bearing AP view of both feet is helpful in assessing subtle injuries and should be obtained if the patient’s condition permits. Computed tomography (CT) should be utilized for the assessment of comminution, in joint depression fractures, and in cases of subtle injury typically invisible on conventional radiographs. Additionally, subtler injuries can occur in specific patterns of Lisfranc injuries such as the base of the fifth metatarsal, which is a common location of a Jones fracture. In these special patterns, CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be needed. A stress test radiography should be completed to confirm the presence of subtle Lisfranc instability and to detect possible biomechanical instability.

After determining the injury mechanism, special attention should be given to thorough physical examination of the foot and radiographic evaluation within a plane of care. Clinicians should examine for the presence or absence of pain on palpation, ecchymosis, blistering, swelling, and symmetry of the midfoot and the severity of the injury. When noting the fracture patterns, a fracture line can frequently be appreciated in a plane of care in the anteroposterior (AP) radiographs or the lateral radiographs. Fracture fragments ought to be stereoscopically struggled and positioned in either the anatomical or close reduction contact positions to confirm congruency after reduction. The size and degree of malalignment of any fractures, articular step distance, comminution, distal fragment tilt, and any intraarticular bone or cartilaginous fragments should be thoroughly assessed. Further, the external appearance and longitudinal alignment, shortening, or displacement parameters of the metatarsals in relation to the medial border of the first metatarsal and lateral border are also needed for a good assessment of the Lisfranc joint. Additionally, the observer must assess the first metatarsal height, obtaining “crrucial points” at the medial and lateral borders, with the use of weight-bearing radiographs. The assessment of the coronoid height, which is typically a 2-3 mm difference between the dorsal and planter surfaces, is also needed.

The following approach to treatment of the various forms of Lisfranc injuries is outlined: Treatment of tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocation, treatment of dorsal fracture-dislocation of the second metatarsal base, direct repair, indirect repair, reduction of dislocation and external stabilization, skeletal traction, closed reduction and percutaneous stabilization, open reduction and internal fixation, plantar-displaced cuneiform fracture sealed, closed reduction, circumferential ankle fixation, ligament repair, late fusion, bone-grafting of titanileta fructloperation, and bony-associated fracture after subluxation. It is important to recognize that the majority of the traditional classifications dealt solely with bony injuries to the midfoot while dislocation of the Lisfranc joint was the main cause of the morbidity of the injury without regard to bony displacement of the cuneiforms. A surgical algorithm, similar to those in other areas of the body that have been well described, can be effectively extended to the treatment of the wide spectrum of Lisfranc injuries while keeping in mind that therapeutic planning must consider restoration of both an anatomic reduction of unstable bones and repair or reconstruction of unstable, possibly ruptured, or intra- and perarticulate ligaments.

There is no consensus regarding the best treatment for the entire Li and Wai spectrum of injuries. However, there is substantial agreement that operative and non-operative treatments both have a position in the spectrum. Non-operative management with a functional treatment plan is reserved for patients with closed, nondislocated isolated ligamentous Lisfranc injuries. Such a treatment plan includes elevation, non-weightbearing short leg plaster cast (or boot) immobilization for six to eight weeks. If the clinical and radiographic results are favorable, the patient can be slowly transitioned to weightbearing and then undergo a program of physical therapy for residual symptoms.

Lisfranc injury type/grade is one prognostic factor for the need for surgery. However, many low-grade injuries can be treated non-operatively. Also serving as prognostic factors for the need for surgical intervention are the location of recognized instability between the medial cuneiform and the second metatarsal, the amount of separation between metatarsal and tarsal bases, particularly between the first and second metatarsal bases, the involvement of injuries or associated soft tissue damage, and the seriousness of symptoms refractory to conservative management. Patients with type-R injuries can generally be treated with conservative care with a good long-term prognosis.

Most authors consider anatomic reduction of the tarsometatarsal joints to be essential to achieve a satisfactory outcome in patients with a complete Lisfranc injury without associated unstable multiple fractures. Open reduction and internal fixation using temporary K-wires, screw fixation, or even external fixation are most commonly used to treat these injuries. Both K-wire and screw fixation have been shown to provide adequate reduction. Although most authors stress that ligament stabilization for primary repair of the plantar ligaments is crucial for proper maintenance of reduction after anatomic reduction, fixation, and ligament repair may be insufficient to maintain reduction and may lead to late loss of reduction. If this occurs, loss of the height of the metatarsal head and subsequent overload of the affected ray may develop. Lindbitch et al. studied the integrity and force absorption capacities of the plantar intramedullary metatarsal ligaments in fresh frozen cadaver bones with damaged tarsometatarsal injuries. They showed that the second ray plantar ligament structures play an important role in absorbing physiologic forces, although they are not critical for stabilizing physiologic anatomic reduction of the Lisfranc joint complex.

The Lisfranc fracture dislocation is a combination of ligamentous and bony injury involving the tarsometatarsal joint of the foot. The cuneiform and the intercuneiform ligament ensure a rigid interlocking of the midfoot bones during the gait cycle. The medial cuneiform is firmly fixed to the base of the first metatarsal by the plantar and dorsal ligaments. These ligaments prevent a dissociation of the first metatarsal from the medial cuneiform, which is crucial for maintenance of the longitudinal arch of the foot. Coughlin found that if a dorsiflexion force is applied to the midfoot when the first and second metatarsals are fixed, a fracture or complete tear of these ligaments will occur. This injury model is similar to a Lisfranc fracture dislocation, suggesting that rupture of the ligaments connecting the first metatarsal to the medial cuneiform is an essential component of a Lisfranc injury. The loss of stability provided by these ligaments is a critical component of a Lisfranc injury, and maintenance of reduction of the first metatarsal with the medial cuneiform is necessary for successful treatment.

Rehabilitation of the Lisfranc injury is similar to that following surgery. After a period of immobilization in a cast or walking boot, a gradual return to weight-bearing is commenced and can take up to three months. During this time, patients may benefit from a single leg heel raise or towel scrunch exercises to maintain strength and prevent atrophy in the calf and intrinsic foot musculature. It is important to avoid excessive swelling of the foot during this period as it will impede rehabilitation, so continued rest, ice, and elevation of the foot is encouraged. Range of motion exercises can be commenced at six to eight weeks providing that there is enough evidence of start of bone healing at the fracture site. Full weight-bearing can be commenced at 10-12 weeks post-injury. An individualized exercise program mimicking that of the surgical patient would then be devised by the physiotherapist focusing on restoring function, strength, and balance of the foot. This may include specific motor control or strengthening exercises, aquatic therapy, and if indicated a gradual return to sport-specific activities.

Without proper treatment or with inaccurate reduction of this injury, patients may suffer from chronic pain and dysfunction of the foot and ankle. In a study by Myerson, the largest long-term follow-up study of missed Lisfranc injuries, 17 out of 21 patients interviewed had pain in their injured foot with increased time on their feet. Pain in the later years was attributed to post-traumatic arthritis of the midfoot with three of the patients having undergone arthrodesis of the midfoot for intractable pain. There is significant evidence that development of post-traumatic arthritis of the midfoot after Lisfranc injury is almost inevitable. In another study by Coss, 67% of patients had evidence of arthritic changes of the midfoot despite anatomic midfoot and/or tarsometatarsal joint and only 33% reporting good or excellent long-term results so patients may experience pain and disability despite anatomical restoration of the joint.

After a Lisfranc injury, chronic pain or discomfort can impede the return of good foot function during daily activities. The amount of pain experienced is not always consistent with the severity of the injury, and some patients with severe injuries have surprisingly little pain. Pain in the Lisfranc joint may be due to arthritis that develops after this injury. The development of both early and late arthritis is common after a Lisfranc injury and this can cause persistent pain and swelling in the midfoot. Patients with late arthritis and persistent pain benefit from rigid type orthotics with a Lisfranc extension or an AFO to limit motion across the midfoot and offload the pressure in this area. An AFO is a custom-made brace that is formed to the leg and foot and can be used to limit motion in the joints of the leg. This can be helpful during the late stages of arthritis when motion across the midfoot worsens pain and inflammation. Patients who develop late arthritis at one joint in the Lisfranc complex but not the others may benefit from a fusion of that joint. Fusion of the joint is a procedure where the articular cartilage is removed and the bone ends are locked together with screws until the bone heals across the joint. Fusion is very effective in eliminating pain at a single joint; however, it also limits motion at that joint. Patients must weigh the benefits of pain relief with the potential functional limitations from restricted joint motion. Late arthritis in the entire Lisfranc complex with severe pain and disability is best treated with arthrodesis of all affected joints. This is a salvage procedure for the painful arthritic foot. The midfoot is compressed and held in a corrected position by screws until the joints heal together. After successful fusion of the affected joints, patients usually have very little pain, although there is some permanent loss of motion in the foot.

Rehabilitation and subsequent physical therapy are critical in an attempt to restore the range of motion in the affected tarsometatarsal joints. A nonoperative approach should include remobilization of the foot with the use of a bone stimulator and physical therapy for range of motion and strengthening exercises of the tarsometatarsal joints. Weightbearing may not be a realistic goal for an individual sustaining a high energy Lisfranc injury, however, an attempt to normalize gait and mechanics of the foot is important in an attempt to decrease stresses across the midfoot. This can be done with or without surgery, but for the former is crucial in an attempt to avoid further degeneration of the joints. If this can be achieved within 3 months’ time and maintained, arthritis can be deferred for many years. If surgically addressed, care must be taken to not stagnate the foot with no remobilization downstream from the fusion. This is a pitfall for many long-term fusion patients and can be magnified when the fusion is extended to other joints of the foot. Postoperative therapy will vary, but should focus around remobilization of the affected joints and return to weightbearing either in a normal or custom orthotic shoe. Simulation of walking in a pool has been shown to be a less stressful, yet effective method for remobilization prior to returning to full weightbearing. This can often be timed or augmented into the above-mentioned bone stimulation therapy as new, more advanced techniques allow for protection of the wound.

For assessment of your condition, please book an appointment with Dr. Yong Ren.